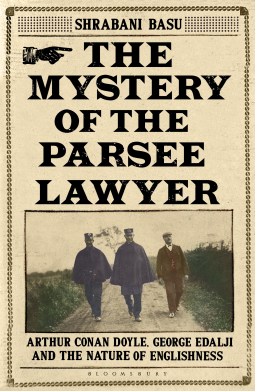

The Mystery of the Parsee Lawyer

Arthur Conan Doyle, George Edalji and the Case of the Foreigner in the English Village

by Shrabani Basu

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date 4 Mar 2021 | Archive Date 4 Mar 2021

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc (UK & ANZ) | Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Talking about this book? Use #TheMysteryoftheParseeLawyer #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

In the village of Great Wyrley near Birmingham, someone is mutilating horses. Someone is also sending threatening letters to the vicarage, where the vicar, Shahpur Edalji, is a Parsi convert to Christianity and the first Indian to have a parish in England. His son George – quiet, socially awkward and the only boy at school with distinctly Indian features – grows up into a successful barrister, till he is improbably linked to and then prosecuted for the above crimes in a case that left many convinced that justice hadn’t been served.

When he is released early, his conviction still hangs over him. Having lost faith in the police and the legal system, George Edalji turns to the one man he believes can clear his name – the one whose novels he spent his time reading in prison, the creator of the world’s greatest detective. When he writes to Arthur Conan Doyle asking him to meet, Conan Doyle agrees.

From the author of Victoria and Abdul comes an eye-opening look at race and an unexpected friendship in the early days of the twentieth century, and the perils of being foreign in a country built on empire.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Hardcover |

| ISBN | 9781526615282 |

| PRICE | £16.99 (GBP) |

Average rating from 5 members

Featured Reviews

Heather R, Reviewer

Heather R, Reviewer

My thanks to the publishers for a review copy of this very readable account of an unsettlingly modern miscarriage of justice, which took place at the turn of the twentieth century.

The book warns the reader it describes cruelty to animals but the crux of this history is about years of repeated, soul destroying, intimidating, mindless and violent racist abuse. It started with anonymous letters and progressed to nuisance deliveries, the planting of stolen goods and forged letters, before leading eventually to the ludicrous accusations linking the vicar’s son, by now a solicitor, with the horrific maiming of horses and his fundamentally flawed conviction.

For George Edalji’s father came from a family of Parsees from Bombay and George was a mixed race boy. His father was the first South Asian vicar in the Church of England. His mother, Charlotte, came from a white English family of parsons. All Shapurji Edalji’s parishioners were white. So, at best the police did not care. At worst, the Chief Constable orchestrated other anonymous letters to entrap the Edaljis and manipulated safe conduct for other potential perpetrators of the crimes.

I was fortunate to have enjoyed Julian Barnes’ Arthur and George, a fictionalised account of the same story, published in 2005, focussing on the disparate lives of George Edalji and Arthur Conan Doyle who championed the campaign to clear his name.

With the benefit of access to letters and other material related to the case, which came into the public domain quite recently, Shrabani Basu has detailed its actual history in the context of its time and the book answers many of the intriguing questions which come to mind. How on earth, for example, did the Rev. Shapurji Edalji, by birth a Parsee in Bombay, wind up in Great Wyrley, where he spent 42 years ministering the faith in the Church of England? What attracted Conan Doyle, a man capable of describing concentration camps as refugee shelters during the Boer War, to take up the case? Where were the fault lines of race and class, which enabled so much liberal support to be mobilised for Edalji after his conviction but meant that he never received any compensation after his release and that he was very quickly forgotten after Doyle’s death.

The book makes commendable efforts to set the action in context as the English Dreyfus case and the perspectives on relevant history of the period are useful. This was the case which more than any other led to the creation of a Court of Appeal.

Some of the black history material mentioned, however, is only tangentially relevant and I suspect it more reflects the author’s other interests and writings.

That apart, this is a good read and shows how little has changed about our institutions of state and maybe our small village life too.

The Victorians and Edwardians may have known a thing or two about industrial innovation and empire building but when it came to detection and policing they were woefully inept. How did Britain's most famous serial killer, Jack the Ripper, escape justice? And what of the innocents wrongly convicted, and sometimes sent to their deaths?

George Edalji would be forgotten today we're it not for the involvement of Arthur Conan Doyle in his fight for justice. His story is a tragedy. A terrible miscarriage of justice. The terrible events in Great Wyrley still unsolved, with more questions than answers.

The author writes with honesty, integrity and compassion. A fascinating, at times gruesome and horrific story of animal mutilation and a family persecuted.

Hilary W, Reviewer

Hilary W, Reviewer

Some readers may have read the novel “Arthur and George” by Julian Barnes. Arthur being Conan Doyle and George being a young solicitor George Edalji who was convicted and given 7 years hard labour in 1903 for mutilating a horse. Basu – in response to Black Lives Matter - has chosen to retell the true story that underlay the novel. How Edalji was released on licence after four years in prison following a campaign for his freedom and then Conan Doyle “investigated” the case and its underlying ramifications, through the national papers revealed his findings, tried to get Edalji a pardon and compensation; running an increasingly bitter correspondence with the Chief Constable of Police for Staffordshire.

Mutilation of animals is a bizarre thing to do – but in the early 20th century a series of attacks were carried out in the Great Wyrley area, where George’s father was parish priest. These caused great consternation and widespread press coverage. But these attacks fed into a deeper local distress as a series of virulent, malicious and frankly seriously odd letters were being sent to people in the village and area. The harassment by letter was in fact a re-igniting of a campaign that had run from the 1880s (when George was a boy) until 1895 when they had suddenly stopped. Edalji’s father, the first victim, had complained to the police who had not been able to resolve the matter. A vicarage servant was sacked but then the campaign started again with physical attacks on the house itself. Rev Edalji wrote to the Chief Constable asking for help and he became incensed at the criticism of his police force, but became convinced that the letters were by young George. In the absence of proof he threatened to “deal with him” in due course. The new parallel campaigns of letters and mutilations were his opportunity. George was arrested and, with a Chief Constable who used all his family and political links, was subject to a seriously flawed trial and was convicted and imprisoned. Meanwhile the crimes continued.

The subtext to all these things is that the Rev. Shapurji Edalji had been born into a wealthy Parsee family in India. Educated for his role in a leading merchant family, he was drawn away at 16 from his family and into the Christian church. Trained as a priest in England, by the late 1877s he had met and married a woman from the north west of England. Through her family links he acquired the living of Great Wyrley becoming the local parish priest for 42 years. They had three children and together they had to adjust to life in poor community part farming and part industrialised (through coal and iron working). A community, it should be said, that carried its own stresses, discontents and rivalries. When the Edalji family fell foul of a serious ongoing feud the question has to be asked as to what tripped it, who was involved (over such a long period of time) and how much of this was the result of the family being non-white. Evidence from surviving correspondence and the newspaper articles indicate that racial discrimination could have been responsible for part of it, and additional tripping the response by people in power, then causing the complete miscarriage of justice that bled out of the village into the legal system and the national government.

As said previously this story – even ignoring the issue of race – is a totally bizarre one. One that not just speaks to the realities of lives for those who are either poor or lacking in other influence or support, but their risks too. Edalji senior was obviously completely out of his depth in this alien place and culture, seemingly expecting to encounter the “politer” theories of respectable British life as opposed to the harsher day to day realities of so many. But this is the place that the family chose to live, regardless, for decades. So it is important to remember the practical realities of this against the inexorable presented “evidence” of reported problems and abuse listed here. But the grinding scale of the harassment makes it hard to see that through this book. The weakness of the book is that the family’s lives and the abuse have become an “issue” here and the day to day aspects of the family’s life are minimised to the occasional odd reference that speaks little to the grim hardship for all the family. It would have been interesting to consider the lives of Mrs Edalji and her daughter in more detail in this place – to explore exactly where they found their consolation, - in the church, or in other members of the community who were “colour blind”. And this at the time when their other son chose to “pass” and walk away. This is a tale that talks to so much of this place, at this time in history, that it inevitably trips demands to know even more. This book, with its severe story, could never be regarded as a comfortable read, but it is a really important one.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Rick Riordan; Mark Oshiro

Children's Fiction, LGBTQIA, Teens & YA